You are reading Ask The Patient by Dr. Zed Zha, a doctor’s love letter that gives patients their voices back. If you enjoy it, please comment, like, share, and/or subscribe!

Dear readers,

I originally planned to write a “clean” version of this story because, let’s be real, if there’s one thing that could get me into trouble with HR, it’s this.

But honestly, I nearly fell asleep writing that version. (And I think you’d fall asleep reading it, too.) (But maybe that would be helpful, too?)

Also, this is my newsletter, so I do what I want. (Kind of. Mostly.)

So, here’s what actually happened.

Think of this story like a medical-themed sitcom—because that’s exactly how it felt when it went down.

Minus the laugh track.

“Dr. Zha, your patient, Erin, is in my clinic. I think she has been picking at her wound.” a colleague, let’s call him John, sat down in the chair behind me.

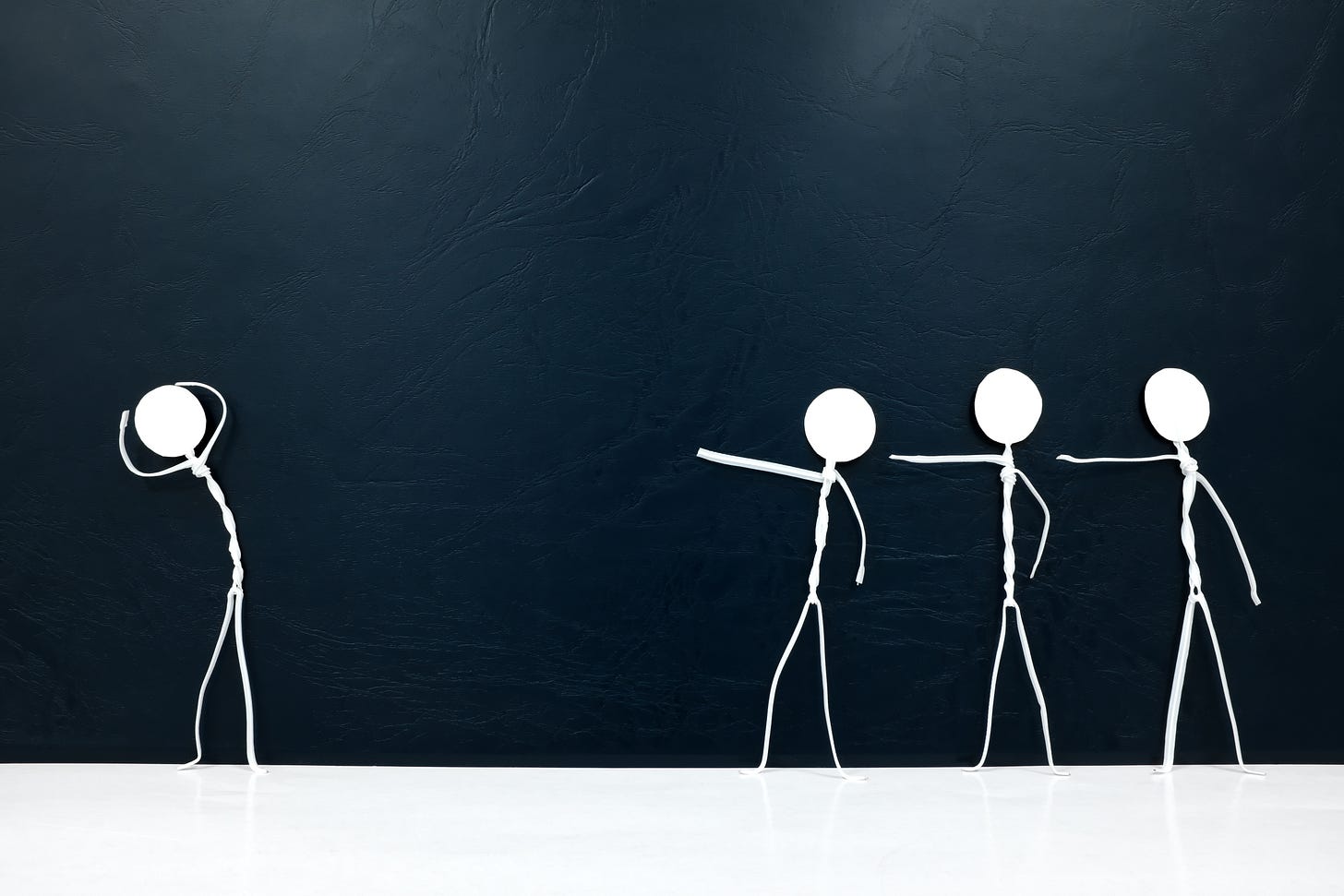

I had heard the story SO many times already: someone has an undesired clinical outcome because of something we (the doctors) did. And what do we do? We blame the patient.

It’s tempting. It really is. Because if it’s the patient’s fault, then we are “off the hook.”

Blah, blah.

But readers, if you know me, you can imagine I was tired of this same old patient-blaming story. Plus, I was already writing to change the story as a (sometimes radical) patient advocate. I had no more patience for it.

“Is she, John?” I sighed before turning my chair around, “What does it look like?”

“Like she’s been picking at it.” John was sticking to the story. Boring.

Erin was a woman in her 60s who had a big cyst on her back that I took out a few weeks before this conversation. The procedure went well and the wound came together very easily. I always give detailed care instructions and tell everyone not to scrub or rub the wound. Plus, I had known Erin for a while by then. She wouldn’t ignore my advice. Even if she did, it was no excuse to blame patients. But for the purpose of storytelling, let’s continue.

“Let me take a look.” I hopped off my chair and started to walk to Erin’s exam room.

Erin sat on the exam table wearing a paper gown for a shirt. The gown opened to her back, exposing her surgical wound and most of her back.

“Hellooooo, Dr. Zha!” After she saw me, Erin gave me her signature big smile.

I loved Erin as a patient. During our procedure a few weeks ago, we played relaxing music and chatted about the plans for her upcoming birthday party. “My grandkids are coming and we are going to paint on a T-shirt together.” Erin was an artist. She told me about how they were going to use Van Gogh’s The Starry Night as a template and put her dog, Vincent, in it. It sounded so fun.

Erin’s daughter, on the other hand, was sitting in the corner of the room with her arms crossed today. She didn’t smile or say hi. I could tell she was upset. I would be, too.

When I examined Erin’s wound, it was obvious that there were two small areas where the wound might have opened up. Overall, it seemed to be healing well. It didn’t look infected. It wasn’t bleeding. But it wasn’t “pretty,” either.

“What happened?” I walked around to face Erin and her daughter, with my back turned to John, because I wasn’t asking him.

“She said it was itchy,” John answered, anyway. Of course. As he said this, Erin’s daughter shifted her weight in the chair. “So, you might have been picking at it?” John was initially standing by the door. Now he inched closer behind me and stuck his head out.

I practiced some grounding techniques to stop myself from rolling my eyes. You know the feeling.

“She didn’t pick.” Erin’s daughter spoke, now shifting her weight forward, arms still crossed.

“Well, maybe not when she is awake…” John continued. Grr. Some people just don’t know how to read the room.

“She is NOT. PICKING!” Erin’s daughter uncrossed her arms and legs and said firmly. I thought she might jump up at some point. Maybe I hoped she would.

“Ok. Ok.” John put his hands in the air and took a few steps back.

I practiced more grounding techniques so as to not give Erin’s daughter a high five for her victory in making John back off. Erin, who knew I was a feminist patient advocate and would never blame (cough *gaslight* cough) her, looked like she was holding back giggles when she watched my self-soothing efforts.

She knew there were 50 ways I had her back.

I nodded at Erin’s daughter then nodded at John. Because I was a professional son of a gun. Then I looked back at Erin and said: “I believe you, Erin.”

She nodded back. Her daughter sat back a little in the seat.

“Would you like to put your clothes back on so we don’t have to talk when you are half-naked?” I asked, emphasizing the words “half-naked.”

A giggle broke through before Erin answered “Yes.” And now Erin’s daughter looked like she was holding back a laugh herself.

“Mmk. Dr. John and I will be right back.” I turned around and signaled John to leave the room with me.

In the hallway, I thought I’d extend an olive branch to John by admitting my own failings. “Yikes,” I made a guilty face, “the wound doesn’t look good, does it?”

You see, I am a young physician. I’ve got room to improve. Lots of it. Sometimes I do a good job. Sometimes I don’t. We all go through 10+ years of training so the former would happen more than the latter. And increasingly so as we live on and learn. But sometimes, sh*t happens no matter how good a job we do. I don’t feel less of a woman one way or another.

But that might just be me.

If John had simply taken the olive branch and pinned the wound complication on me by saying something along the lines of “Yeah Zed, your work sucked,” or “It looks terrible, maybe do better next time,” I would have smiled and said something like “Yep, my bad, thanks (but no thanks) for covering for me (by blaming the patient)!”

But he didn’t. Of course not.

“Well. I’m sure she’s picking a little. And…” John kept digging into the hole. Poor guy. Still trying. “And the nurse who took out the sutures probably took them out too early. If she knew what she was doing…”

“OK, John!” I held out a hand to stop him. I’d heard enough.

Scapegoat a woman (the patient) once, I may not say anything because, who knows, maybe he did it to protect my “ego.” But scapegoat yet another woman (this time, a nurse)? Please don’t do it on my behalf. My “ego” doesn’t deserve you!

“We don’t talk about our colleagues like that anymore, OK?” I told John. Actually, we don’t talk about our patients like that anymore, either. But baby steps.

We were standing in a busy hallway, and people were passing by like it was a Monday morning at the coffee shop. Our conversation wasn’t exactly private. As I slightly turned up the volume of my voice, John crossed his arms and went into defense mode.

“Well, but it’s true!” John protested.

Someone, please, hold my earrings — because I was about to let him hear it.

“John, are you saying you know EXACTLY what you are doing EVERY TIME you see a patient? You’ve never made a mistake or been wrong before?” It was a silly thing to say, honestly, because even if he was “perfect” at his job, it still didn’t give him the right to blame others for something that could happen to the best of us.

“Well…no but…” he started to mumble. “But better than her!”

I am NOT good at reasoning with five-year-olds. I should have created some space and emergency-texted my therapist to ask for more grounding techniques. Or maybe go gargle some water. Or eat a piece of cake. But there was no time. Or cake. Just a whole medical culture to change in this one hallway

“John…” I squared up. I trained for this. I was ready for this. Here it came. “…don’t be a jerk.”

Dont. Be. A. Jerk?

All my years of British parliamentary-style debate training, feminist advocacy, OpEd writing, and medical cultural critiquing…boiled down to these four words. Don’t be a jerk. Everyone should be so proud of me now. Not.

There might as well be some whistling wind blowing snow around in the hallway. Because that was how cold the air felt.

“I’m ready!” Erin opened the exam room door and stuck her head out. THANK GOD SHE DID. I swear I saw her shiver when the frozen tension hit her.

I’d love to think that my “I believe you” cheesy line was what disarmed Erin’s daughter because when we came back to the room, she was no longer looking defensive or pissed off. But Erin probably said something to her. If she did, I hoped it was something like “Stop it, Dr. Zha is on our side!”

Because I am. #TeamPatient all the way.

“Erin, I am so sorry this wound doesn’t look good.” I fought the urge to follow this sentence with a “but” or a “because.” I knew doctors were known for our inability to sincerely apologize. I wasn’t going to offer another non-apology to another patient. So, I paused and let my words land. This way, I wasn’t asking to be let off the hook. I stayed on the hook, so to speak.

“Oh! Pss!” Erin made a sweeping gesture with her hand as if she was slapping away a fly, “it’s finnnnnnne! It gives me character!” She already had a character. A wonderful one.

“Really, Erin, I’m sorry…” I wanted to make sure she heard me. I also wanted to make sure John heard me and saw that we didn’t turn into stones immediately if we just took some ownership of our clinical outcomes. Or, in the words of my mother, you won’t end up with less rice in your bowl by putting down your pride.

“Ok,” Erin’s daughter cleared her throat. I thought maybe I should brace myself for an actual slap. “Now, you’ll have to turn around and let Mom see your blouse!”

“My blouse?” I was confused.

“Yes! Your blouse.” Erin’s daughter sounded excited. Her body language had completely changed. She was now at the edge of her seat pointing at my jacket.

Oh!! My jacket! I forgot I was wearing a jeans jacket style top I bought from Spain, Pablo Picasso’s home country. The shirt was hand embroidered with one of the faces from his famous painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon). It was my favorite!

“Oh, my goodness. Of course!” I turned around to point at my shirt and told them the story. “That reminds me…Did you have fun at your birthday party? You have a picture of the shirt you and your grandkids painted?” I asked.

Sure, Erin was a patient with a wound that didn’t look good. But before Erin became a patient with a wound, she was an artist who painted Vincent on a T-shirt, Van Gogh style at her birthday party!

From the corner of my eyes, I saw John slowly exit the room as we chitchatted. He walked sideways one step at a time like some sort of awkward crab.

“Thanks, John!”

That stopped him mid-action. He looked at us. We waved him goodbye.

John isn’t actually a jerk.

Maybe John isn’t even real. Maybe he’s just a reflection of the old me because I was that jerk once.

I learned how to be a jerk from other jerks who came before me. I watched them get away with their jerky behavior, and I saw how no one ever really held them accountable—because the only thing getting hooked was our egos and our demons.

I passed that same lesson on to others. I taught them how to be jerks by being one myself.

Maybe, on (hopefully) rare occasions, I still am a jerk.

But here’s the thing: the patient-blaming, the staff-blaming, the scapegoating so we can stay squeaky clean, the making others small so we can look big culture—it’s all too common in medicine.

And it’s time for us to wave it goodbye.

Luckily, I have worked with/am working with many colleagues and I know many fellow physicians and clinicians who are not jerks—who are true self-reflectors, patient advocates, and compassionate professionals.

And if you think we’re going to sit back and let jerks continue to walk all over our patients, our coworkers, ourselves, or our profession…

…think again. 😈🤘

Loved all of this—and particularly this: “Or, in the words of my mother, you won’t end up with less rice in your bowl by putting down your pride.”

So many doctors I’ve encountered are jerks. Listening needs to be taught in medical school