The Self-Blaming Patient

And the lessons I learned from him.

The thing about patient blaming is that if you do it long enough and often enough, the patient will start to believe it.

A few months ago, Kevin, a 38-year-old man came to see me for a “rash” he had had for over 15 years. When I came into the room, I recognized it was no small rash, but severe plaque psoriasis.

“Doc, I screwed up,” Kevin said as soon as I walked into the exam room.

If the phrase “I screwed up” had a signature posture, Kevin embodied it perfectly: his elbows on his knees, and hands cupping his face. The other thing that demanded attention about Kevin was his general appearance. Kevin wore torn-up jeans (not the fashion statement type, but worn out); there were food residues on his shirt; and he smelled like he hadn’t showered for days.

“I screwed up.” His buried face and muffled voice made him sound like a little kid who did something wrong.

There are many common phrases I hear patients say about their psoriasis.

“I stay up all night scratching myself silly/until I bleed.”

“The tube of cream the doctor prescribed was way too small.”

“I can’t do more creams, I need something stronger,” are some common ones.

And “I screwed up” doesn’t typically make the list.

“Can you tell me why you said that?” I asked. Skipping introductions was not very AIDET of me. But Kevin needed us to cut to the chase.

“Every time I get dirty, I break out in this rash. I’m allergic to dirt!” Kevin sounded matter-of-fact. “And I knew that. But my furnace broke, so I had to go into the crawl space to fix it. I should have asked my buddy to do it! I should’ve known better!” Kevin briefly looked up at me and returned to his defeated posture.

Dirt allergy? Is this a delusion? But something told me that Kevin was not delusional. At least it was not the whole story.

“Kevin, who told you that?” I followed my hunch.

Turned out, when Kevin was diagnosed with psoriasis 15 years ago, it was after he fell. He scraped his knee, which did get dirt on it. Shortly after that, he developed a rash around the wound. Then plaques spread from there like white flakes covering the ground on a snow day.

While psoriasis lesions like to form at the site of injury (the Koebner phenomenon), psoriasis isn’t caused by the injury, or the dirt on the injury. It’s a thing that just happens to the best of us. But I could see how someone could make the connection.

My immediate reaction was to correct this “false belief,” as I wished the clinicians before I had done: “Kevin, listen,” I paused to wait for him to look at me, “you getting dirt on your skin didn’t cause you to have this condition. What you have is called…”

“That’s not what the other doctors said!” He cut me off.

“I know but…” I tried to continue.

“I’ve had this for 15 years. Believe me, I KNOW what causes it. I JUST have to be more careful.” Kevin interrupted me again. And this time, he raised his voice and almost sounded annoyed.

If there is one thing that has always made me mad, it’s a man who wouldn’t let me finish my sentences. In general, women are more likely to be interrupted when they talk, often by men. And being a woman of color in medicine means I am often dismissed or discredited compared to my male colleagues in this traditionally male-authored and dominated field.

So, being interrupted by a man triggers me. Kevin’s interruptions and his raised voice were no exceptions. I felt the urge to yell back.

But in recent years, I have been working on humility in and outside the exam rooms. Plus, if my Twitter (otherwise known as X) polls #AskThePatient have taught me anything, it’s that it’s not enough to only hear what patients say.

You have to really, really listen.

So, what was Kevin saying?

“I’ve had this for 15 years. Believe me, I KNOW what causes it. I JUST have to be more careful.”

This wasn’t some disinhibited misogyny like my brain wanted to assume defensively. This was something else. And it wasn’t about me at all.

I’ve had this for 15 years.

Interpretation: I’ve suffered for a long time. I am at the point of desperation.

Believe me, I KNOW what causes it.

Interpretation: I need someone to believe in my suffering and respect that I know my own body.

I JUST have to be more careful.

Interpretation: I need to believe that there is something I can do to help myself feel better. I want to stop feeling out of control.

In other words, Kevin needed to believe that he wouldn’t have to be tormented by this diffuse and painfully itchy rash for the rest of his life.

Looking through Kevin’s charts, he had had many visits for his psoriasis. Sometimes it was correctly diagnosed as psoriasis. Most other times the notes said, “rash,” “allergic reaction" or “tinea corporis” (ringworms), which were all common mimickers of psoriasis. When creams were prescribed, they were of a very small quantity — not nearly enough to cover his whole body.

While Kevin had been frequently misdiagnosed, one of these misdiagnoses stuck the most: dirt allergy. Due to Kevin’s firm belief in this, he probably offered that explanation to the clinicians as soon as they walked in the door, just like he did to me. Then the clinician’s unfamiliarity with the severe rash pushed them to find the “easy way out”: sure, dirt allergy makes sense!

Voila, Kevin’s false belief was solidified by the white coats time after time.

But there was another reason why Kevin had been self-blaming. And it’s one of medicine’s not-so-well-kept secrets: patient blaming. Encounter after encounter, Kevin had been blamed by the medical team for not being careful enough or not taking care of himself. And for someone who looked as “unkept” as Kevin, it was easy, even “natural” to do so.

Patient blaming is common and harmful.

More than half of patients feel shamed or blamed by their physicians. Being blamed by anyone — a friend, a family member, even a stranger online — is very stressful. Now imagine when the blamer is your doctor, in front of whom you are totally powerless and vulnerable, and whom you trusted to help you feel better. Not surprisingly, one in five patients leaves their doctors for this reason.

How about the remaining four out of five patients? Though there isn’t clear data on this, it isn’t hard to imagine that some buy into this illogical idea that their medical condition is their fault. Why? Because people pay to hear the opinions of a doctor — someone who went through a decade of higher education to do what they do. And if their opinion is, “This is your fault,” it must be true. Right?

Wrong.

Other than being unethical, unhelpful, and untrue, patient blaming is also lazy medicine.

When Kevin offered the “I fell into some dirt therefore now I have a full-body rash” story, the clinician latched onto this convenient theory without exploring other possibilities. This is termed anchoring bias, and it facilitates premature closure of clinical reasoning — the very thing that patients pay us to do.

At the same time, if the solution is simply “just don’t get dirty next time,” then the responsibility of improving health outcomes falls on the patient instead of the physician-patient team. And when patients don’t get better, it must be because they haven’t been diligent enough to avoid dirt. The prescription is, naturally, “try harder this time.” Rinse, then repeat.

This insidious form of recycling false information gaslights the patient into self-blaming.

The diet culture is the master of this tactic. The multi-billion dollar industry relies on people’s assumption that they aren’t thin yet because they haven’t adhered to the diet and exercise regimen sold to them, even though there is a large body (pun intended) of evidence showing that long-term weight loss is almost impossible.

Common gaslighting slogans we hear diet culture influencers say are: “You are not tired. You are uninspired.” “Carbs are the enemy.” “Do this if you want your summer body!”

Over my bread body, I say.

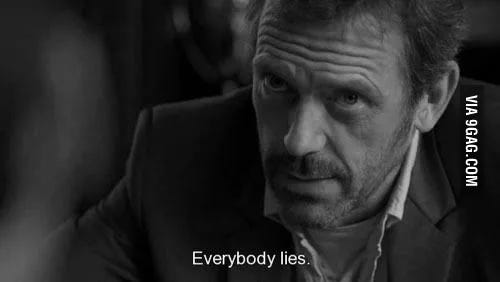

To be fair, unlike diet culture where the industry financially benefits from selling a lie, most doctors don’t blame patients consciously or intentionally. In fact, as an insider, I can attest that there is a patient-blaming culture in medicine that is really to blame for this harmful phenomenon. Remember the famous quote by the jerk/genius diagnostician, Dr. House, from the 2004-2012 popular TV show? “I don’t ask why patients lie. I just assume they all do.” It’s more than just a punchline made for dramatic effect. This patient-blaming culture is deep-rooted in the history of medicine and passed down to generations of practitioners.

Assuming patients haven’t done what they were told therefore sabotaging their own clinical progress is a tale as old as medicine itself. Hippocrates urged physicians to “keep aware of the fact that patients often lie when they state that they have taken certain medicines." This absurd assumption that patients somehow don’t want to get better is still alive and well in today’s medical education (thankfully, in a more subtle form).

“Ok, Kevin. I believe you.” I meant it, too.

I didn’t believe the theory of dirt allergy. But I believed that it had been the truth for Kevin for many years. And that is not something I could change the first time we met.

“I still think you have psoriasis. But you don’t have to agree with me. Let’s try something. And if you don’t get better, we will add to the treatment plan or try another approach.” By now, I was squatting on the floor so I could be at Kevin’s eye level when he decided to look up.

“OK. Am I seeing YOU next time?” Kevin asked with a weird emphasis on “you”. For a moment, I was sure he said this because he wanted to fire me.

“If you want, I will follow up with you until we get you better.”

“OK, doc. I will give this a try and we will see in a couple of months then.”

Kevin went on to apologize for being “argumentative.” I dittoed what he said. Finally, I think we were on the same team. I explained the risks and benefits of the treatments I offered and I was not interrupted by Kevin once more.

It occurred to me after my visit with Kevin that it really didn’t matter what the “truth” was when it came to a diagnosis. It mattered more whose truth it was. We all just want to feel better and get on with our lives. And in the end, even though Kevin didn’t buy into my diagnosis, he agreed to give what I offered a try.

So in a way, perhaps he did believe me.

Disclaimer: patient identity and case details have been significantly altered to protect confidentiality.

love the substack. I have been told my backpain was all in my mind, because I didn't look suffering, or walk with a limp. Even I didn't recognize my face as a suffering patient when I looked in the mirror as it was calm, relaxed and looked fresh. Thanks for writing these.

The heading felt right out of Sherlock Holmes.