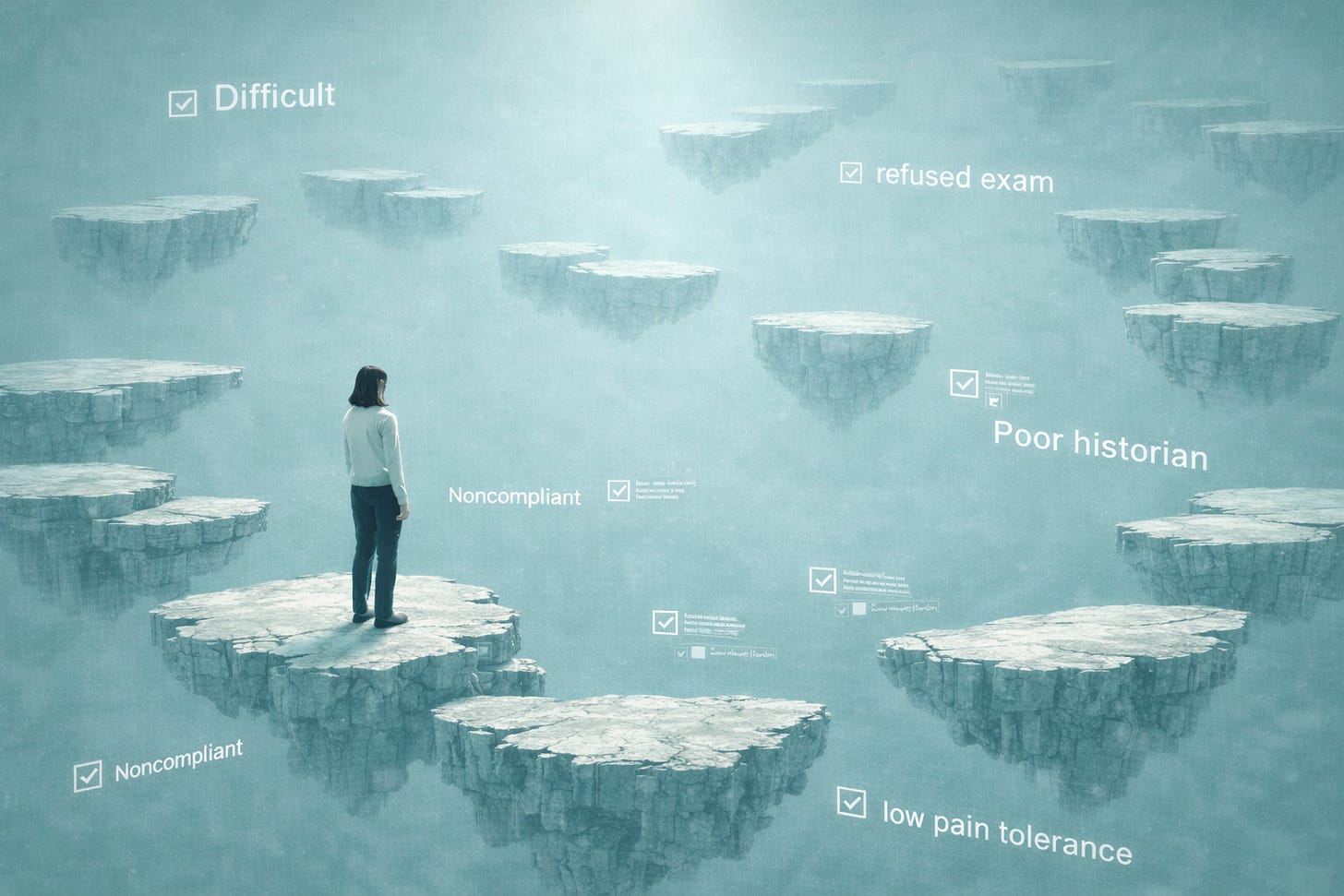

The Difficult Patient

When Agency Gets Diagnosed as Noncompliance

There are certain feelings that follow you out of a “difficult” patient’s room. I’m going to name them here. It’s a frightening thing to do, I must say, to sit with those feelings and not flee.

So please, stay with me.

The Inaccurate Note

“I noticed that you wrote ‘patient had adverse reactions to the medication’ in your note,” Kristina said, MyChart open on her phone, her top leg bobbing at the edge of the chair. “And that’s not accurate.”

In the movie version of this story, the doctor would be an old man in reading glasses. The glasses would slide down his nose as he stared, stunned, at the young woman daring to challenge his authority.

But this was not a movie. And I was no old man behind a desk. (I also do not possess the kind of nose capable of catching falling spectacles.) I was a young doctor who had written an inaccurate note and whose patient had caught it.

I felt the fork in the proverbial road immediately.

I could play the doctor in the movie. Or I could be who I claim to be: a feminist patient advocate, a physician who believes medicine should be accountable and patient autonomy should be radically respected.

I wanted desperately to be the latter. But my ego, my training, and the century-old hierarchy of medicine tugged hard toward the former. I felt my face heat up.

“Oh, shoot. I’m sorry,” I said, sitting down and turning my laptop toward myself. “Can you remind me what actually happened?”

“Well, I didn’t have a reaction,” Kristina said. “The medicine just didn’t work.”

Her leg kicked faster. I scooted my stool slightly out of range and nodded, my face burning beneath tinted sunscreen and a mask.

She’s not saying you failed, I reminded myself. She’s saying the medication failed.

“I see,” I said, re-reading the line in my note. She was right. “I must have mistaken it. Thanks for pointing it out. I’m happy to make a correction to the note.”

Her bobbing leg slowed. Then it stopped.

My face was still hot. But it cooled with the realization that the real-life version of me had won the tug-of-war against the movie doctor. And that felt right.

I think Kristina agreed. For the rest of the visit, she sat comfortably, legs uncrossed, in a chair more than large enough for her body. We talked through next steps and agreed on another plan.

The Difficult Patient (Me)

I sometimes wonder if I’m a difficult patient.

“So… patient refused exam,” Nick said carefully, enunciating for the AI scribe.

A flash of panic tightened my chest.

I take a strong medication for alopecia areata ophiasis, a severe, treatment-resistant autoimmune hair loss condition. On the day of my follow-up visit with my doctor (and colleague), Nick, I was working in the same clinic. It was a procedure-only day, so I came to my appointment during lunch, in scrubs and a surgical cap.

Nick walked in with his laptop. Behind him trailed a medical student with — and I hate to say this — excellent hair. After brief pleasantries, Nick asked me to remove my cap so they could examine my scalp.

You know the shampoo commercial: the woman on the motorcycle, the dramatic helmet removal, the cascading hair?

She doesn’t have alopecia areata.

For those of us who do, showing our hair is a big deal, even to our doctors.

I’ve had this illness since I was eight. I was called “the ghost girl,” “an egg with hair,” “an upside-down broom.” When the teasing stopped, the unsolicited advice began: The water must be too hard (like that’s not a literal oxymoron), try black sesame-based shampoo (should I switch to lotus root when my hair turns gray?), or, the real gem: stop being so stressed. (I’m not even gonna entertain this one with a snarky comment in parentheses.)

So, yeah, I’ve spent my life hiding my hair: under hats, powders, wig clips. And no, I was not prepared that day to reveal my scalp to a stranger with offensively good hair, especially when it was matted and messy under surgical headwear.

“No,” I said, gripping my cap with both hands as if my scalp were my most precious asset. “I have to go back to surgery in a minute. I don’t want to take it off and put it back on.”

Lame, I know. But it was the best I had.

Nick blinked. His brain worked through the anomaly: a patient refusing an exam. Then the recognition: this patient was also a colleague. He glanced at the student, who offered a small shrugged.

“So… patient refused exam,” Nick said to the scribe software.

Translation: the patient is being difficult. I knew the language well. I speak it fluently myself.

That’s how I became the difficult patient.

And if “difficult” appears this quickly for me with my credentials and my insider status, what happens to patients without those protections

Now Who’s Being Difficult?

So, who gets labeled “difficult?”

Well, it’s not random. Studies show that they are more likely to be women, older adults, people living in poverty, people of color, trans people, people with mental health conditions, chronic illness, disabilities, multiple or unexplained symptoms… see the pattern?

These are precisely the patients whose bodies didn’t come straight out of a textbook written by people who don’t look like them or whose lives don’t fit neatly into a fifteen-minute visit.

These aren’t difficult people. They are people facing difficulty.

Strange they would come to us for help, isn’t it?

When we look at the other side of the interaction — the clinicians — the pattern really sharpens. Clinicians are more likely to label patients difficult when they are overloaded, under-resourced, poorly supported, short on time, uncertain, inexperienced, or worried about impressing others. Trainees are especially vulnerable, particularly if a patient threatens their sense of competence.

Honestly? That’s just about all of us.

In other words, “difficult” doesn’t describe the patient. It reveals a collision within the clinician:

Complexity vs. capacity,

Context vs. the clock,

Real people vs. a system that demands simplicity.

Disabled patients have been naming this for years. In her piece, My Most Dangerous ER Experience and How My Advocate Saved My Life, Disabled Ginger describes how this collision becomes life-threatening: worsening symptoms minimized, pain dismissed as “normal,” having to perform illness to be believed, basic tests delayed until an advocate forced action.

What was probably labeled as pushiness was, in fact, survival. And what looked like excess was actually urgent needs misunderstood, neglected, and mishandled.

The stakes were much lower in my own case: a subtle shift in tone when I declined an exam and the sense of a label hovering over my stubbornly covered head. But trauma doesn’t need to be spectacular. Sometimes dignity erodes slowly, until autonomy becomes something you must actively defend.

Difficult? No.

Life-preserving. Autonomy-reclaiming. Absolutely.

And here’s the most uncomfortable statistics: the majority of patients are perceived as difficult at some point.

That includes Disabled Ginger.

That includes you.

And me.

That Uncomfortable Feeling

After I left Kristina’s exam room, my medical assistants said, “Wow, you spent a looong time there. Everything ok?”

“Yes,” I answered, “she’s just –”

I searched for an adjective. But the only ones that surfaced were ones the movie-doctor would use. Then the real-life version of me shook her head and asked: Whatever word I choose (probably some variant of “difficult”), is it really relevant to her care?

And even if it were (it isn’t), who am I to define her?

Indeed, when we label patients difficult, these are the words that appear: rude, demanding, aggressive, manipulative, hostile. Notice these aren’t clinical facts. They’re feelings.

Our feelings.

Definition: A difficult patient is someone who provokes strong negative feelings in their clinician: frustration, irritation, anxiety, uncertainty, often triggered when patients collide with our limits, our knowledge gaps, or the illusion of our authority.

In short, difficult patients exist outside our comfort zone.

And that makes us uncomfortable.

Looking back at my patient labeling days (and I hope they are past me), what unsettles me most is how many of the so-called difficult patients were women. Consented is, in many ways, my attempt to claw myself out of that special place in hell, by telling the truth about how easily medicine confuses discomfort with danger, and control with care.

Writing about medicine has made me a better clinician precisely because it has forced me to look inward. And if you’re going to write a book, I mean really write one, there’s only one way to do it: tell the truth, even when it implicates you.

So, healthcare folks, let’s stop asking: Why are so many patients difficult?

Ask instead: Why are we so uncomfortable when patients don’t follow the script?

And isn’t it time we ditched the script altogether?

Ask The Patient

Over the coming weeks, I’ll keep writing through moments like this, tracing what it has taken to see medicine differently, and what it has cost not to. Until we name the ways medicine violates patient autonomy, the road forward will remain difficult.

If you’re here, you’re already part of that reckoning.

Have you ever been labeled “difficult?” (The answer is yes.) How did that label shape your care?

If you choose to share or comment, know this: in this space, stories are held with care. I would be honored to hear from you. 🩵

Subscribe to Ask The Patient

A growing community trusted by over 3,700 readers.

I’m Zed Zha, MD, a physician and medical cultural critic writing about harmful medical culture, consent, and bodily autonomy. Here, I write to name what patients feel but are rarely given language for, and to imagine what care could look like if we listened differently. Join me.

I asked my pain mgmt doc for an MRI of my post-op knee that was CRANKY and huge and not healing according to the prescribed timeline. She said she didn't want to step on the surgeon's toes and declined. So I went back to the surgeon and asked him to order the MRI, explained why, and he did. When I brought the results to the Pain Doc, she said, and I quote "Huh - you're a stubborn one." Not tenacious, determined, persistent - no - none of those more positive adjectives - I was 'stubborn'. I still think about that almost 10 years later.

This is timely, I was just reviewing my file history looking up anything to do with heart and BP as I just had a Tilt Table Test and was waiting for results and if there was anything to bring to my physician.

It turned into a rabbit hole of remembrances of gaslighting.

Like the time I was labeled with dependent personality trait as after years of seeing a counselor I was still going

because I was being treated for depression and never had remission.

Trusted and trialed 17 antidepressants. Over 14 years.

So a new Psychiatrist finally listened to my ‘fatigue is just part of depression’ and diagnosed me with ME Myalgic Encephalomyelitis.

Also the clinical psychologist diagnosed Autism.

Both explained so much. I do not get back my depression years but going forward I can thrive.

Back to too many appointments = dependence. I asked how they came to that conclusion and one point it was because I never missed an appointment.

I did not miss appointments before depression but was not asked.

I did a supervised exercise program and reported it made my depression worse.

When my psychiatrist said just do 20 of cardio three times a week I did say I am not doing that but would continue with what worked for me as was given another note of “doing things her own way” and not a compliment.

For example that at I would not do anything 2 days before my appointment, and often after it would take a week to recover my energy.

But most importantly I was never asked for details on my fatigue.

The Starbucks I brought to my appointment was ordered on the app and picked up at the drive through and was most likely a meal replacement as preparing food was too difficult.

Anyways I finally am that difficult patient. And not apologizing for seeking answers or seeking to correct the record.

At the Tilt Table test appointment I was able to Depression off my conditions in MyChart and replaced with ME Myalgic Encephalomyelitis.

( that had it’s own biases but that is another story )